Shear strain is a crucial mechanical parameter that every engineer must understand in order to properly analyze deformations in materials and structures.

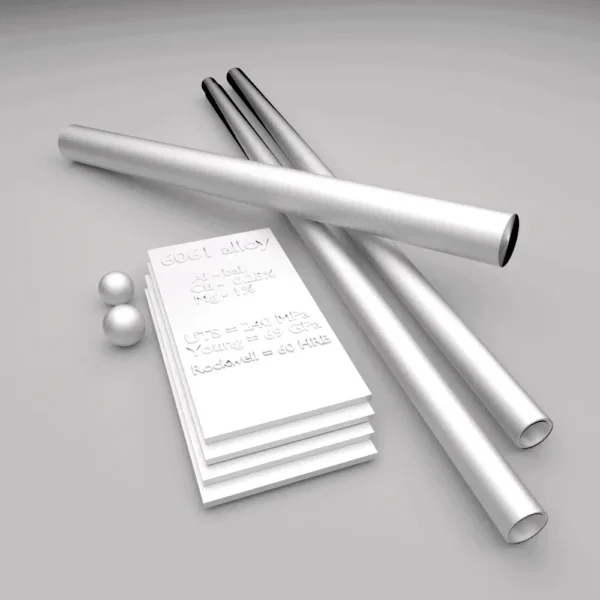

It is an important concept in materials science and structural engineering.

It refers to the geometrical distortion that occurs when applied forces cause internal shear stresses within an object.

Specifically, it quantifies angular change by measuring how much a right angle distorts into a parallelogram under shear loading conditions.

Compared to normal strain from tensile or compressive forces, shear strain results in more complex directional deformations.

Accurately determining this strain allows calculation of torque and predictions of material failure limits.

What is Shear Strain?

It refers to the angular distortion that occurs when a material experiences shear stress.

Specifically, it measures how much a right angle deforms as opposing parallel forces are applied.

To visualize this, imagine a rectangle changing into a parallelogram due to shearing forces.

The strain quantifies the resulting change in angle.

It is calculated by dividing the angular change by the original right angle.

In summary, it measures the degree of shape deformation when shear stresses cause parallel planes in a material to slide.

Deriving the Strain Formula

The formula can be derived geometrically based on a shear strain diagram showing the distortion of a right angle:

Where:

θ = Original right angle

Δθ = Change in angle due to strain

The shear strain γ is calculated as:

γ = Δθ/θ

Expressed as a percentage, this becomes:

Shear Strain (%) = (Δθ/θ) x 100

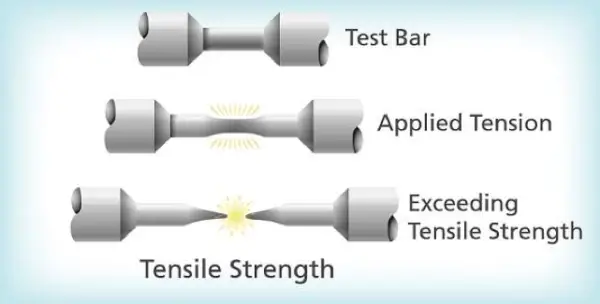

Key Differences Between Shear Strain and Shear Stress

While related, shear stress and shear strain have distinct meanings:

- Shear Stress – Tangential force per unit area that tends to cause deformation

- Shear Strain – Amount of shape change caused by shear stress

In simpler terms, shear stress is the cause while strain is the effect.

Key differences also include:

- Shear stress has units of pressure (Pa, psi). Shear strain is dimensionless.

- Shear stress reaches a peak value before material failure. Shear strain continues increasing until failure.

Understanding how these two parameters relate gives greater insight into material properties and behavior

Step-by-Step Calculation

Calculating strain involves four key steps:

- Identify original and deformed dimensions of the material.

- Determine angular distortion with basic trigonometry.

- Subtract original from distorted angle.

- Divide angular change by original angle.

For example, consider a 10 cm x 10 cm square material under shear stress:

- Original angles = 90 degrees

Distorted angle ∠A’ = 60 degrees - ∠A’ = tan-1(8/12) = 60 degrees

- Δθ = 90 degrees – 60 degrees = 30 degrees

- γ = Δθ/θ = 30/90 = 0.33 = 33% shear strain

This quantifies the strain for this shearing deformation case.

Examining Strain Tensors and Matrices

For more complex 3D analysis, shear strain tensors and matrices are used. These mathematical tools capture multi-axis shear strains within an XY material plane.

The tensor endpoints convey maximum positive and negative shear strains. Principal strains show where shear strain is directly aligned with material coordinates.

With transformed matrices, tensor axes can be manipulated to simplify calculations.

This facilitates analysis of shear strain in materials experiencing complex real-world loading.

Applications in Structural Beams

Accounting for shear strain is vital when designing beams and joints in structures like buildings and bridges.

In beams it can lead to dangerous stress concentrations and cracking failures if not properly addressed

By considering beam geometry, shear force diagrams, and shear strain formulas, engineers can calculate expected strains and incorporate reinforced web designs to withstand shear forces.

Proactively mitigating shear stresses enables safer structures with longer service lives.

The Role of Strain in Geology

In the field of geology, analyses of shear strain improve understanding of plate tectonics and seismic activity.

Within Earth’s moving crust, strain occurs across fault lines and helps characterize associated landforms like plateaus.

Strain markers visualize and quantify historical deformation patterns along geological formations.

Data on buried shear zones also provides insights into hydrocarbon systems, reservoirs, and potential drilling locations.

For geologists, strain analysis is imperative for deciphering the powerful forces continuously shaping our dynamic planet.

Graphical Representation

strain data is often conveyed visually using graph

Key aspects include:

- Proportional limit – Shear stress and strain are initially directly proportional, following a linear relationship.

- Yield point – The point at which material deformation transitions from elastic to plastic.

- Failure point – When material fractures under shear loading.

Plotting experimental data as stress-strain curves shows material properties and aids in comparing performance across test specimens.

Performing Unit Conversions

As a dimensionless quantity, it has no specific units.

However, when expressed as a percentage, unit conversion is still sometimes required.

To convert strain percentage to decimal form, simply divide by 100.

For example:

Shear strain of 28% = 0.28

Converting between other units like millistrain (10-3) follows the same format using an appropriate scalar.

Real-World Examples

Some physical instances where strain manifests:

- Deformed rebar in a shear wall resisting lateral building loads

- Tilted layers exposed in a road cut through deformed rock

- Jagged cracks in a steel I-beam under transverse loading

- Offset walls and door frames in homes after earthquake shaking

- analyzing DNA with gel electrophoresis stretching

The variety of examples highlights its broad relevance across science and engineering fields.