When it comes to the longevity and safety of buildings, the underpinning of foundations is a critical process that homeowners, engineers, and builders should understand intimately.

Underpinning refers to retrofitting an existing foundation to improve its load-bearing capacity, stability, and performance. It involves installing new foundation elements underneath or around the existing foundation structurally tied to them.

Underpinning is undertaken when foundations fail or show distress, need retrofitting to support additional loads, or suffer movement needing restraints. Techniques range from conventional hand-dug pits to large bored piles and even innovative methods with polymer injection port structures.

From addressing structural problems to accommodating changes in use or soil conditions, underpinning is the key to maintaining reliable and sturdy foundations.

In this guide, we’ll explore what is underpinning a foundation, delve into multiple underpinning methods, including cement foundation underpinning and concrete underpinning, and provide expert answers to common questions such as how to underpin a foundation and what is pinning in construction.

What Is Underpinning of Foundations in Construction?

Underpinning in construction is the process of strengthening and stabilizing the foundation of an existing structure. The primary goal is to extend the foundation’s footprint or depth so the load can be repositioned onto stronger and more stable soil layers or bedrock. Common situations that require the underpin foundation process include:

- The original foundation is insufficient—in size, depth, or composition.

- Changes in the use of the building, leading to increased loads.

- Altered soil properties (e.g., due to subsidence, moisture shifts, or surrounding construction).

- Structural distress, such as settlement, cracks, or movement caused by natural disasters like floods or earthquakes

Types of Underpinning Methods

Here are the main types of underpinning methods:

- Hand-Dug Underpinning

This traditional underpinning method involves manually excavating pits and trenches to access the foundations. The new underpinning concrete footings or piles are then constructed in these pits and connected to the old foundation. - Mass Concrete Underpinning

This method pours large continuous volumes of concrete below the original foundation rather than individual footings. Temporary casing tubes may be used when pouring the underpinning concrete to prevent collapse. - Mechanical Underpinning

Mechanical underpinning employs powered percussion, vibration, or rotation systems to drive or drill new piles or piers with minimal digging. Techniques like driven cast-in-situ piles, helical screws, and vibro-displacement columns fall in this category. - Micro Piles

Small-diameter steel-reinforced piles that can be quickly drilled into soil using hydraulic drilling rigs characterize micropile underpinning. High-pressure cement grouting then provides stability. - Chemical Grouting

Chemical grouting improves subsoil density and properties by pressure injecting expanding resins or polyurethanes without needing access pits. This stabilizes soils for improved bearing capacity.

The underpinning method is selected based on structural deficiencies, site constraints, access for machinery, soil conditions, groundwater levels, and substructures needing retrofitting. Engineers customize the approach based on application suitability.

Why Is Underpinning the Foundation Needed?

Some typical reasons for underpinning foundations include:

- To strengthen settling or shifting foundations.

- To allow for an additional story to be safely built.

- When a nearby excavation threatens the stability of existing foundations.

- As an alternative to demolition and reconstruction of the entire building

Underpinning Detail: How the Process Works

How to Underpin a Foundation – Step by Step

- Assessment: A careful site evaluation is performed. A structural engineer determines the cause and extent of foundation problems.

- Design: The appropriate underpinning method and detail are selected based on soil conditions, building requirements, and budget.

- Execution: Portions of soil beneath the foundation are excavated in carefully sequenced procedures. New reinforcing materials—such as mass concrete or mini piles—are installed.

- Load Transfer: The building’s load is gradually redistributed to the new support system.

- Monitoring: The work is monitored for settlement and stability, ensuring long-term performance.

Underpinning Methods: Explore Your Options

Understanding underpinning methods helps you select the right approach for each scenario:

| Underpinning Method | Description | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Concrete Underpinning | Excavate sections beneath foundation, fill with concrete, repeat until full depth/length achieved. | Shallow foundations, traditional buildings |

| Mini Piled Underpinning | Small-diameter piles driven deep into strong soil; connects to existing foundation with concrete caps. | Restrictive or poor soil conditions, deep loads |

| Beam and Base Method | Reinforced concrete beams are constructed below existing foundation and supported by new mass concrete bases. | Where lateral load distribution is needed |

| Jack Pile Underpinning | Jacks and piles support foundation during construction, then permanent piles take over. | Heavier structures, rapid solutions |

| Root (Angle) Piling | Angled piles drilled beneath foundation for enhanced support. | Sites with obstructions, variable soils |

| Pynford Stool Method | Needle beams and steel support stools used to transfer loads during underpinning. | Long continuous walls or space constraints |

Key underpinning detail: Each method requires specialized engineering design, safety measures, and regulatory compliance.

Cement Foundation Underpinning and Concrete Underpinning

Cement foundation underpinning and concrete underpinning are often used interchangeably. Both involve adding new concrete (with or without steel reinforcement) beneath or beside the existing foundation, thereby increasing its strength and distributing loads more effectively.

Mass concrete underpinning is the most traditional and cost-effective solution, favoring sites with moderate load and shallow depth requirements.

Underpinning of Existing Foundations: What to Watch Out For

Underpinning the foundation of trusted articles and buildings should always be guided by a qualified structural engineer who:

- Performs a thorough soil and foundation assessment.

- Designs the underpin foundation according to site specifics.

- Oversees execution to minimize risk, structural movement, or accidental collapse.

- Documents all underpinning detail—important for future property sales or insurance claims.

What Is Pinning in Construction?

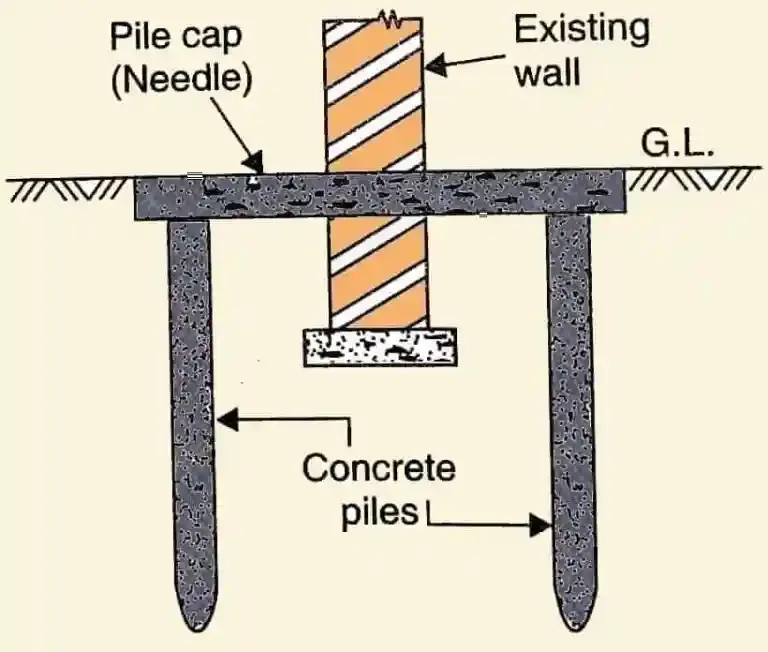

In the context of underpinning foundations, “pinning” refers to inserting steel, concrete, or timber “pins” (also called “needles”) through a supporting wall. This allows foundation loads to be temporarily supported while excavation or repairs are performed under the wall. After underpinning is completed, these pins are either removed or left in place

When to Carry Out Underpinning

Common indicators that underpinning should be considered are:

- Foundations fail bearing capacity verification checks for increased working loads

- Existing foundations undergo excessive settlement or tilt/rotate markedly

- Lateral foundation movement observed owing to adjacent excavations or slope erosion

- Structure needs restraints against swell, heave or vibration susceptibility

- Water infiltration or chemical aggression affects foundation integrity

- Structural retrofitting goals require strengthening connections to foundations

The trigger for underpinning is generally either actual foundation failure or prevention for an existing structure that needs capacity enhancement.

Pros and Cons of Foundation Underpinning

Advantages

- Strengthens foundation capacity and factors of safety

- Arrests ongoing settlement issues

- Provides robust lateral and uplift restraints

- Technically superior to surface structural repair alone

- Enables further vertical expansion of buildings

- Safer in liquefaction-prone seismic zones

Disadvantages

- Disruption to site access and activities during works

- Specialized skill sets required for design and execution

- Difficult quality control in subsurface works

- Debris/slurry handling needs arrangements

- Risk of vibration/ground loss impacts to adjacent buildings

Structural Monitoring for Underpinning

Robust structural health monitoring serves to:

- Establish a pre-construction baseline of foundation performance through tiltmeters, crack gauges, load cells, and precise level surveys. This is critical forensic data.

- Ensure foundation movements remain within safe limits during temporary works and pile installation to minimize damage risks. Thresholds for vibration and deformation are predefined.

- Confirm satisfactory post-construction foundation performance via repeat surveys and instruments. Monitoring continues until stabilization milestones are achieved.

Temporary Works Design

Due to invasive subsurface activity risks during underpinning, temporary works provide critical stabilizing supports:

- Sheet Piling: Cast-in-situ walls retain soil stability for basement digs that expose foundations for pile cap connection works. They also reduce groundwater ingress.

- King Posts: Hydraulic supports brace basement slabs during temporary soil excavation periods. This prevents uncontrolled slab movements.

- Casing Pipes: Serve as stable void formers that allow safe boring of piles while preventing surrounding ground collapse.

Robust temporary propping systems are mandatory before undertaking foundation strengthening modifications.

Step-by-Step Underpinning Procedure

A standardized underpinning workflow comprises.

- Detailed structural and geotechnical site investigations

- Laboratory soil testing and development of underpinning basis of design

- Installation of monitoring instrumentation

- Sheet piling retaining wall placement with king posts or casing pipes

- Excavation in sections and stabilization with supports

- Drilling/chiseling for pile installation sequentially

- Pile cap and grade beam construction

- Grouting and stitching works

- Rebuilding of floor slabs/walls tied to new underpinned foundation

- Curing, instrumentation monitoring and validation of underpinning

The procedure necessarily adopts a bottom-up approach, stabilizing deeper foundation layers before upper rebuilding.

Specialized Underpinning Equipment

Typical equipment for underpinning comprises:

- Sheet Pile Drivers: Powerful cranes insert interlocking retaining wall piles around areas to be underpinned.

- Hydraulic Excavators: Equipped with rock breakers and munchers to expose foundations for underpinning.

- Bored Piling Rigs: Augered piles in soils use continuous flight auger (CFA) rigs that can drill up to 1.2 m diameter piles in soil/weak rock.

- Vibratory Hammers: For stronger stone/rock, excavator-mounted vibro-hammers can sink casings to allow piled foundation installation.

- Grouting Pumps: Cement or chemical grout injection is done using high-pressure positive displacement pumps that can inject into narrow soil pores also.

- Level Monitoring Systems: Precision laser/radar systems track building movement to mm accuracy during underpinning.

Minimally Invasive Underpinning Methods

In congested sites with restricted headroom for traditional underpinning equipment, the following techniques serve well:

- Compaction Grouting: This injects calibrated cement grout at pressures up to 35 kg/cm² to densify granular soils without needing access pits. Concrete piles can still be inserted through the improved ground.

- Polymer Injection Piles: Modified polyurethane foams are injected through small-diameter ports to create dispersed underground micropiles. As injections fill fissures, they expand, generating strong reinforced soil pile clusters.

- Jet Grouting: High-velocity fluid jets erode subsurface soil, which is replaced by simultaneous cement grout injection through the jet nozzle under pressures exceeding 100 kg/cm². This produces soilcrete with pile capacities over 400 tonnes.

These specialized techniques enable underpinning even in confined sites like building corners or without excavation access. Smaller rig footprints, lower headroom requirements, and remote operations aid applications.

Typical Underpinning Depths

Common underpinning design guidelines recommend:

- Piled Foundations: Bore pile tips minimum 1.5 m into bearing stratum resistant to erosion and consolidation. Typical pile lengths range from 5 m to 15 m.

- Pier Foundations: Base keying 300 mm into the bearing layer but at least 900 mm total depth into stable soils.

- Chemical Grouting: Soil improvement by compaction/polymer grouting extends to the 95th percentile influence zone estimated from test injections.

Actual underpinning depths vary based on structural loads, soil properties, and factor of safety targets. Deep, stable soil zones must support the structure for the long term.

Common FAQs

How do I know if I need underpinning?

Signs include cracks in walls, uneven floors, windows/doors not closing, or visible foundation movement. Always consult a structural engineer or geotechnical engineer.

Can I underpin my foundation myself?

Underpinning is a specialized task. Improper execution can cause partial or total collapse. Always hire certified professionals.

What is the most affordable underpinning method?

Mass concrete underpinning is usually the least costly, but only suitable for shallow issues. Complex or deep foundations may require mini piles or beam and base methods.

Conclusion

Underpinning serves as a robust foundation-strengthening solution for existing buildings by installing new structural supports underneath tied into the original foundation system.

This comprehensive guide covers underpinning methods, site assessment, pros/cons, sensor-based monitoring, specialized equipment, workflow, and innovative techniques for congested sites.

With sound underpinning engineering, settlement- or capacity-deficient foundations can be retrofitted, leading to substantial structural integrity enhancement and extended building lifespan.